»Every vow you break,

Every smile you fake,

Every claim you stake,

I’ll be watching you.«

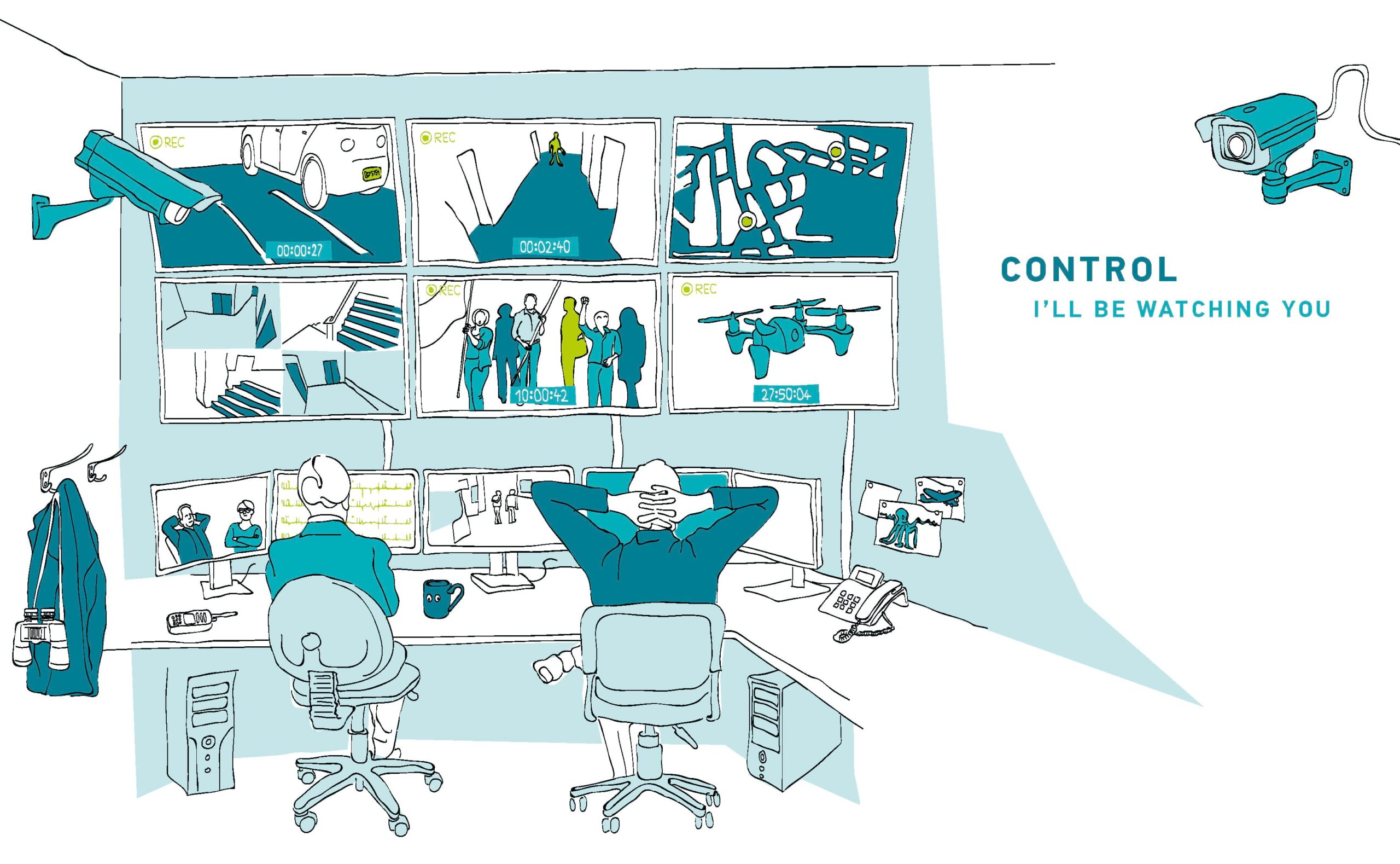

This verse from the song »Every Breath You Take« by the English New-Wave band »The Police« is accompanied by a simple and catchy melody. Someone listening to the text off-handedly might think he is listening to a very normal love song. But in fact the song is about a person that is relentlessly controlling his own girlfriend. Sting, the singer and bassist of the band, wrote the song in 1982 at a time when his marriage was in its last throws. He described his thoughts about the text of the song in an interview: »I didn’t realise at the time how sinister it is. I think I was thinking of Big Brother, surveillance and control.« The feeling of being controlled at every turn, of having to disclose every secret, all the most private thoughts, is undoubtedly dreadful. »Total control«, whether it is between individual people or within a state, is used again and again as a dramatic theme in movies, computer games, books and, yes, even songs.

Of course for all that, control is also a necessary function that is fundamental to our individual and social lives. In this sense, control consists of all the visible and invisible techniques, strategies, methods and institutions that a society utilizes to bring about certain behaviours in the populace. The family, the school, the church, but also laws, traffic lights or even the time of day are forms of control that serve to discipline people. Seen in this light, control enables an orderly co-existence among people in a society. There is of course another perspective from which control can be considered, one that stems from the concept of power.

If someone knows something about another person, he has power over him. It thus follows that surveillance is a means of attaining power and influence or, in a word, control, which is the power to manage people´s behaviour. But the whole enterprise of surveilling and managing requires that specific and relevant information about persons be ascertained. Surveillance consists of a whole palette of different practices and procedures, from pure observation to gathering and recording data and, finally, making identifications. The British sociologist David Lyon sees surveillance as »any collection and processing of personal data, whether identifiable or not, for the purposes of influencing or managing those whose data have been garnered«.

What is clear is that the goal of surveillance is to manage behaviour. A controlling authority may use its influence to steer people towards a certain goal, towards thinking and acting certain ways. This can be done directly through things like education and legislation but can also be accomplished in indirect ways like, for example, through propaganda or advertising. Moreover, control can also be exerted by isolating and sanctioning behaviour that deviates from desired or accepted norms. A criminal is sentenced to jail time or an entire country has its Internet switched off – as happened in 2011 during the Arab Spring in Egypt. In order to assess an instance of control it is therefore important to consider the framework within which it is being exerted. What purposes does the control serve? What kind of adverse consequences are involved? Does it seem to be manipulative or supportive?

Control has always been correlated with various forms of technology, the material instruments used for monitoring and managing. Looking back in human history it becomes apparent that the introduction of any new means of communication always brings new strategies of monitoring and control in its wake. Thus, for example, in the mid-19th century many European countries prohibited the use of encryption methods when transmitting telegraphic messages in order to maintain supervisory access to the contents. In Prussia, telegraph companies were even required to make and save copies of every message. Technological monitoring constantly has to be supplemented with new techniques because the mass of data that is being collected from various sources has to be analysed and processed. An automated management system is required. Furthermore, networks linking different monitoring techniques and control methods are often created. Pictures from a surveillance camera, for example, can be readily used in conjunction with automatic face-recognition technology and algorithmic comparisons to population registers.

Governmental control

The prototypical example of the exercise of control – of monitoring and managing – is the state. The origins of modern day state control go back to the 17th and 18th centuries, which was when the modern political state emerged. Shortly after the disastrous experiences of the Thirty Years War the idea that the sovereign was responsible for the security and well-being of his subjects became widely accepted. The state became the entity that defines the common good of all citizens by enacting universally valid laws and being the sole power for enforcing them. The French philosopher Michel Foucault has pointed out that the means employed for this have subsequently comprised a system made up of monitoring, punishing and educating.

States have continually defined the common good in disparate ways. In liberal-democratic states the manner in which the common good and the related maintenance of public order and safety is achieved is substantially different from that found in a dictatorship. Thus National Socialism employed a racist ideology as the basis of the common good while socialistic regimes justify their supervisory powers with the dogma of the »dictatorship of the proletariat«. The military, police or security services are the traditional government institutions for exerting control irrespective of their being a democracy or dictatorship.

It was, for instance, Division 26 of the Ministry of State Security in the GDR (»MfS«) that was responsible for monitoring the telephone calls made by opposition groups and persons. That agency relied mainly on audiotapes and, later, audiocassettes for its technical telephone surveillance but the technologies for the analysis and data management were not equal to the job. By the end of the 1980s »MfS« analysts were hardly able to keep pace with the purely manual transcriptions and evaluations of the wiretapping tapes. This circumstance also illustrates an inherent progression in the history of technological surveillance: As ever more complex and comprehensive communication networks are developed, the number of individuals that can be monitored increases as well until finally mass surveillance is possible.

Technologies and procedures such as wiretapping telephone lines, identifying people by means of biometric data, video surveillance, data retention, or the continuous and unjustified surveillance of the Internet since the beginning of the 21st century demonstrate the state´s claim to a monopoly on competence and omniscience. This claim becomes manifest every time there is a conflict between the governmental mandate for both establishing security and maintaining civil rights.

The control function, however, not only works from top to bottom – from the state down to its citizens – but rather in the reverse as well. It is not unusual in liberal democratic societies for single individuals or civil society groups to become the surveillants of the surveillants. Whether this is accomplished by raising the awareness of the state´s transgressions of the law or by taking legal action against those transgressions or by protesting against the misuse of personal data: This »power from below« must be taken into account by a democratic constitutional state. Thus, for example, the establishment of a legal basis for data protection in the Federal Republic of Germany was achieved through just this power.

Economic control

The state with its security and organizational methods is, however, not the only player in the game of monitoring and managing. Commercial enterprises likewise employ the strategies and techniques of surveillance in order to manage the perceptions and behaviour of consumers. The job of »marketing« is to offer products and services for sale in such a way that consumers perceive them as desirable and worthwhile.

The rise of marketing can be traced back to the end of the 19th century. The Industrial Revolution brought with it far-reaching economic and social changes and facilitated a major expansion in the mass production of goods, which were differentiated by certain design features. Customers had more choices and competition between companies increased accordingly. There was a growing consensus among entrepreneurs that products had to be positioned in the marketplace in such a way that customers would refrain from choosing another comparable product. Hence the next decades of the 20th century saw the development of marketing strategies whereby the companies concentrated their attention specifically on the customer.

Companies were better able to establish methods for promoting customer loyalty by being better informed about consumers through the analysis of their buying practices and their credit worthiness based on empirical research procedures, communication strategies, mathematical predictive models and psychological theories. Technological developments were central to this enterprise. The supplanting of paper file cards by electronically stored data in the second half of the 20th century, as well as the increasing networking of information technologies, opened up totally new possibilities for analysis and prognoses in the commerce, finance, insurance and human resources management sectors.

One essential method for developing customer information is social sorting, which David Lyon described in 1994 as the constant ongoing classification and sorting of the populace through the use of information technology and algorithms based on personal data. Twenty years later, Lyon´s conceptions have become reality. The Internet and digitalization have enabled digital surveillance to become nearly ubiquitous. Information about things like age, gender, sexual orientation, political attitude, religious conviction or even drug addiction and alcoholism is automatically generated when someone simply clicks a »Like« on Facebook. While more and more devices and objects are equipped with sensors that record user behaviour, companies continue to develop even more fields of application and expanded business models. »Big Data«, which refers to the consolidated techniques of automated analysis and evaluation of enormous amounts of data, enables companies to create personality profiles for individuals simply from records of their daily behaviour patterns, preferences and dislikes.

This information leads to individualized offers and differentiated prices that are geared to the consumer´s profile, whereby the companies are indeed capable of controlling and steering the perception of users. The American lawyer Michael Fertik has shown that this dynamic has already resulted in the rich having a much different experience of the Internet than the poor. Thus, for example, Apple computer users will be shown higher hotel prices than users of cheaper brands. The potential for discrimination in vital matters like credit worthiness, healthcare, work and insurance is clearly a real danger. The companies´ communication and information channels that users find so convenient are in fact anything but neutral. Companies, it turns out, are solely motivated by economic concerns and are only accountable to the principle of maximizing profit.

Self control

The individual person is not only an object of control. In many ways the individual can also be an agent of control, of monitoring and managing, as well. This observation led the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze to his idea of the »Societies of Control«, in which the individual is also a controller and every situation is potentially a control situation. Individuals not only control their fellow humans but themselves as well: People create an effective public image of their own personality. They then use the resulting image, which is also being continuously renewed, to guide and control the perceptions that others have of them. This public self-image is used to proclaim one´s own uniqueness and to assure one´s membership in a particular group while also being the means of convincing others about oneself and one´s own viewpoint.

This is clearly illustrated by the different forums and platforms required for the dissemination of one´s own image in the public sphere. In pre-digital times, letters-to-the-editor writers expressed their self-image and their views in the printed newspaper while today people have social networks like Facebook in which they can stage-manage and oversee their pubic self-image and effectively control the way it is perceived. Or take the platforms of the Quantified Self movement: The sensor-controlled monitoring of one´s own body produces volumes of data that are willingly being shared. What in the past was explicitly private is now made available for public evaluation. Here it is no longer the state, the school or the church alone that insist on conformance with the norm, but rather the individual himself that disciplines his own behaviour to comply to a given set of norms, many of which have been established by the marketplace. Self-control with regard to the individual thereby appears as a key society-building practice.

And what about technology? The development of new technologies has an enormous influence on the multifaceted social as well as individual control situations. A self-reinforcing dynamic underlies the power of technology to exert influence. Technology creates new needs and thereby initiates a transformation in the handling of personal data and privacy. Control – monitoring and managing – is thereby directly connected to the technological disruption currently taking place, the digital revolution. In other words, the new digital technologies cannot function without bringing control procedures in their wake. To be sure, all techniques of control – regardless of whether they stem from state or economic institutions – are constantly being put under legal restrictions in democracies in order to prevent the scope of control situations from becoming total. But that is not enough; it is also imperative that every person learns new coping strategies for dealing with the public information sphere in order to be able to act as a digitally competent citizen and consumer.

Published in: Stiftung Deutsches Technikmuseum Berlin (Ed.): Net Matters. 30 Stories. From Telegraph Cables to Data Glasses, Berlin 2018.

Translation: Barry Fay, Lost in Translation

Illustration: Polygraph Design

Literature:

Aumann, Philipp: Control. Zwischen staatlicher Überwachung und Selbstkontrolle, in: Das Archiv. Magazin für Kommunikationsgeschichte, No. 3/2013, pp. 7–17.

Christl, Wolfie: Kommerzielle digitale Überwachung im Alltag, 2014. (accessed 17.10.2017)

Deleuze, Gilles: Negotiations, 1972–1990, London. 1997

Fertik, Michael: The Rich See a Different Internet Than the Poor, 2013. (accessed 17.10.2017)

Fleisch, Elgar/Mattern, Friedemann (Eds.): Das Internet der Dinge – Ubiquitous Computing und RFID in der Praxis, Berlin 2005.

Foucault, Michel: Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison, New York 2012.

Gaycken, Sandro: 1984.exe – Gesellschaftliche, politische und juristische Aspekte moderner Überwachungstechnologien, Bielefeld 2015.

Lyon, David: The Electronic Eye: The Rise of Surveillance Society, Minneapolis 1994.

Lyon, David (Ed.): Surveillance as Social Sorting: Privacy, Risk, and digital Discrimination, London/New York 2003.

Lyon, David: Surveillance Studies: An Overview, Cambridge 2007.

Schaar, Peter: Das Ende der Privatsphäre. Der Weg in die Überwachungsgesellschaft, München 2007.

Standage Tom: The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s On-Line Pioneers, New York 1998.

Trojanow, Ilija/Zeh, Juli: Angriff auf die Freiheit: Sicherheitswahn, Überwachungsstaat und der Abbau bürgerlicher Rechte, München 2014.