Apparently everything began with a gimmick used by US American railway ticket collectors. In the second half of the 19th century they punched tickets at specific points in order to make a record of a passenger´s special characteristics: gender, skin colour, and so on. This was to prevent different persons from using the tickets numerous times. This practice prompted the engineer Herman Hollerith to come up with the idea to use the same method – in standardized and automated form – for the US census taken every ten years. Hollerith had worked on the tenth US census in 1880 and knew the difficulties being faced by the Census Bureau: The analysis of millions of questionnaires was in the meantime taking several years. But what would be the effect if part of that work were to be done with machines? Wouldn’t that reduce the analysis to a fraction of the time? And wouldn’t much more differentiated results be possible with the use of the punch-recorded characteristics?

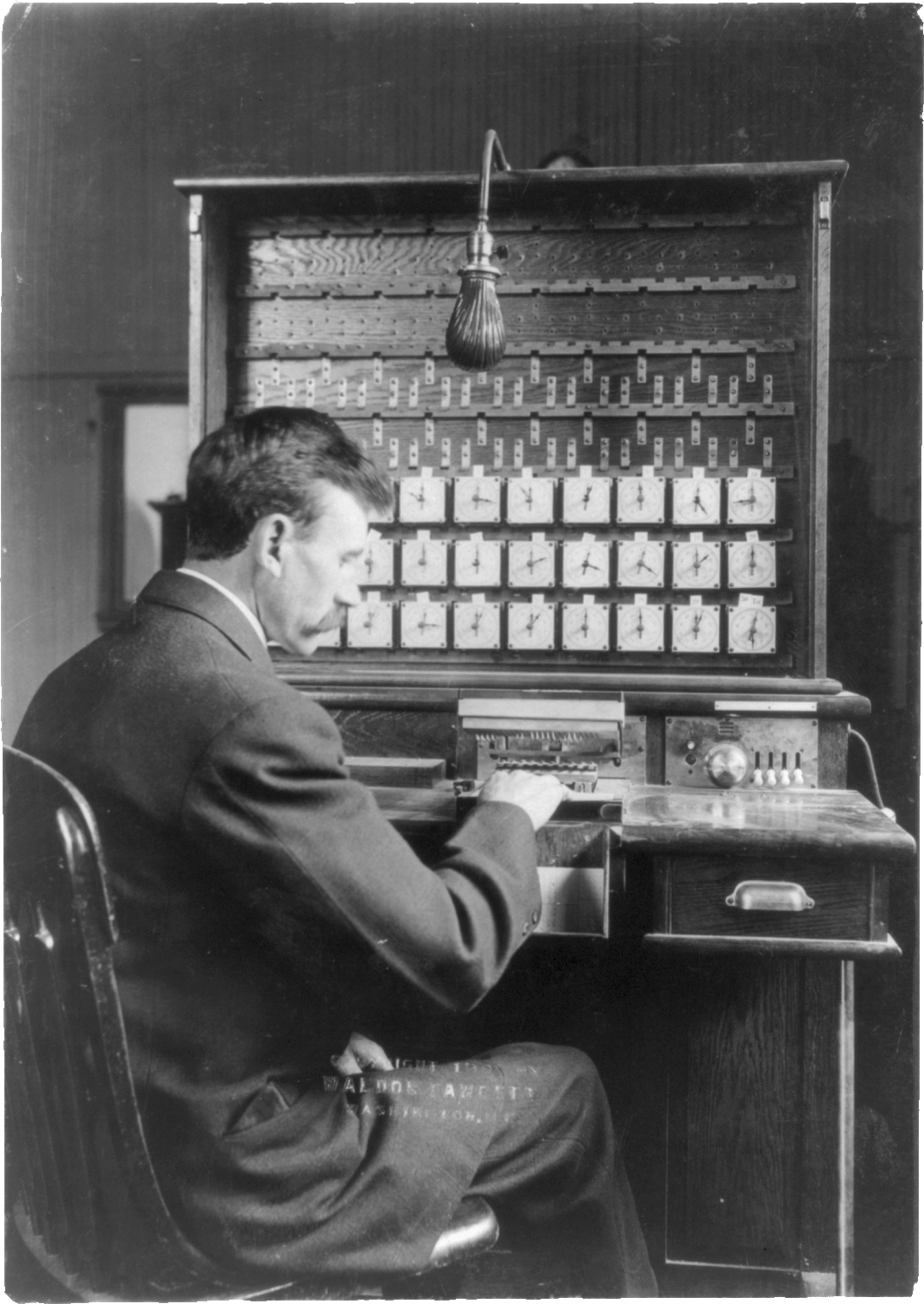

The Census Bureau lost no time in initiating a competition addressing the question of how to improve the evaluation of census data. And the winner was: Herman Hollerith. His patented punchcard was at the core of his proposal. At that time punchcards were not really new: They had already been used in the 19th century to operate looms, barrel organs or mechanical pianos. What made Hollerith´s punchcards different, however, was that they stored data instead of control commands. The railway ticket collector´s gimmick was to be used on all the inhabitants of the USA – producing concrete information and attributes in the form of punchcards. The punchcard system that he developed, as well as the complementary counting machine, was thereupon utilized in the eleventh US census of 1890, but its impact was not limited to census procedures.

Counting with holes

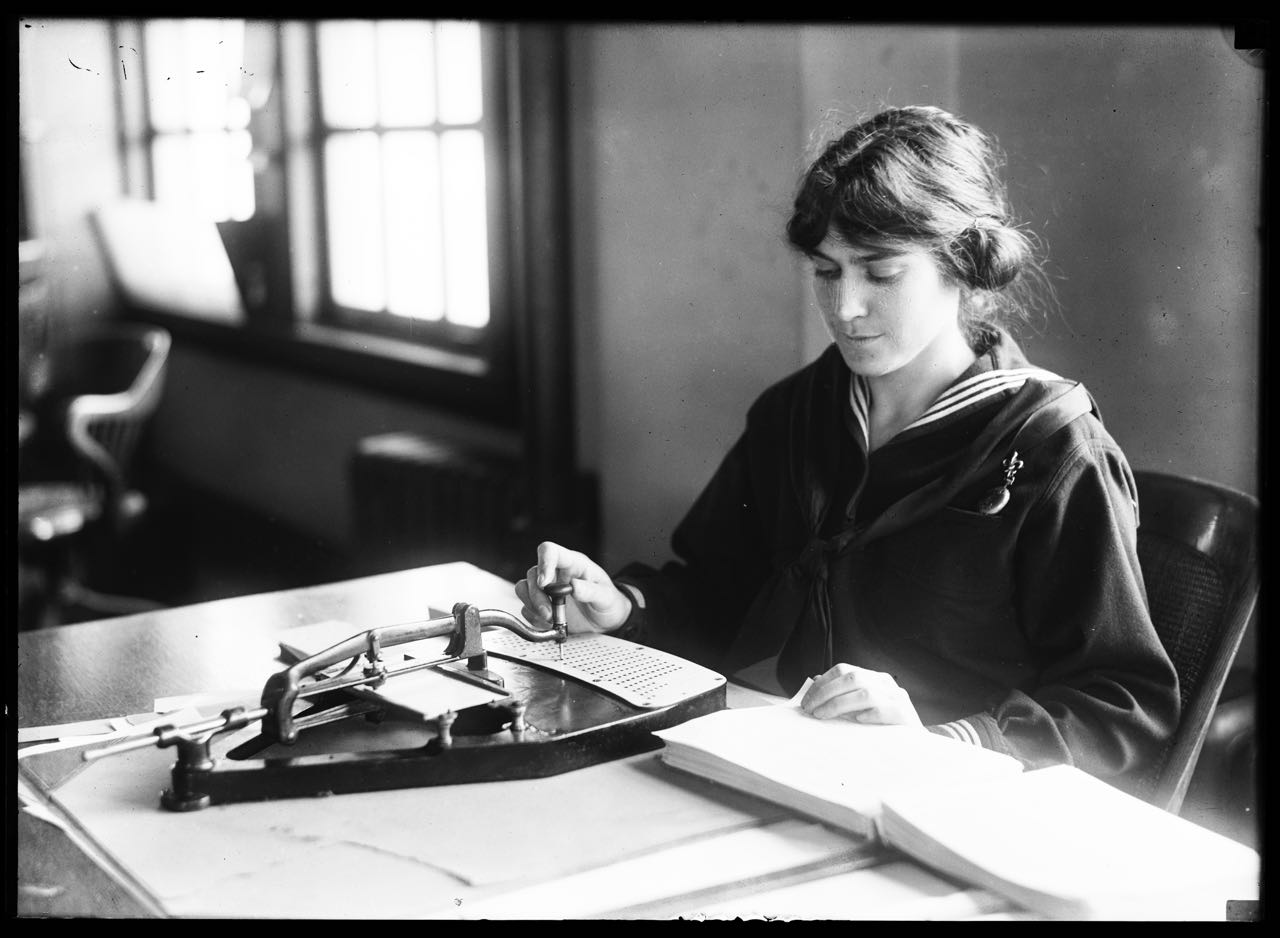

Female workers used hole punches to transfer the information from the compiled family questionnaires onto millions of punchcards – one card for each person. The strong cardboard was divided into 24 columns and 12 rows. Each hole punched in a field meant »yes«, every missing hole meant »no«. Is the person female? Married? Can he or she read? Is the skin colour black? Entries like age – for example between 20 and 30 – were punched into fields covering groups of ten. The counting of the punchcards was performed by an electro-mechanical apparatus that was likewise devised by Hollerith, a tabulating machine, 43 of which were put into operation. And the population figures were indeed available in a few weeks. There were 62,947,714 people counted.

The ingenious feature of Hollerith´s counting machine, however, was something else. Through its use, not only the total number of cards could be counted but the cards could also be sorted into groups according to several criteria and those groups counted in turn. This enabled differentiated statistical data to be collected. If someone wanted to know, for example, how many white, unmarried men between 20 and 30 years of age live in New Jersey, that info was readily available – at a speed that seemed unimaginable. For this, each punchcard was slid into a sensing device, a reader. Where there was a hole in the card a spring-loaded pin would dip into a well of mercury and thereby complete an electrical circuit that activated a switching device and the pointer of a recording dial. The working conditions, which entailed caustic mercury vapour, paper dust and piecework, were unfortunately anything but healthy. The female workers were known to blow some paper dust into the mercury bowl on purpose: The electrical current would be disrupted; the maintenance man for the machine would have to come and refill the bowl. Looks like a good time for a breather!

Hollerith machines on the advance

Despite such incidents all the statistical analyses was completed in only a few months. Herman Hollerith had brought about a great success. He continued to make improvements on his machines. Soon enough, the process of inserting the punchcards was no longer done by hand but was instead automated. Renowned for his choleric disposition, Hollerith began quarrelling with the Census Bureau almost immediately. Word of his success, however, had quickly spread. Other countries now wanted to use his sorting method for their own populace. Customers from the business world were also standing in line. In 1896 he founded the Tabulating Machine Company. His business plan worked out: The machines were rented out at a relatively low price as the real profits came from selling the punchcards.

In 1911 Hollerith withdrew from his business and sold his company. It was amalgamated with other companies to form the Computing Tabulating Recording company (CTR), which was renamed International Business Machines (IBM) in 1924. The Deutsche Hollerith-Maschinen Gesellschaft mbH (DEHOMAG), which initially leased Hollerith machines and sold punchcards as a licensee, had been established in Berlin as early as 1910. During the German inflation of 1922 its license fees increased to an unaffordable level and CTR, or later IBM, consequently took over ninety percent of the company. DEHOMAG remained a subsidiary company and in the following years enjoyed the greatest possible autonomy. In the 1920s and 1930s it was especially successful in the areas of research and development.

Calculating with holes

The functional demands being made on the tabulating machines steadily grew. It was already clear in Hollerith´s time that commercial enterprises were interested not only in tallying, but to an even greater extent calculating: Account management as well as bookkeeping and inventory management require addition and subtraction processes. Invoicing, payroll accounting and interest calculation are not possible without multiplication and division. Little by little the tabulating machines were equipped with new functions. In the 1920s and 1930s they were already a long way from Hollerith´s prototype: No more toxic mercury, but instead automated card readers, electromagnetic arithmetic-logic units, exchangeable switch panels and data output by means of line printers. Even the punchcards had changed. They now had more rows and columns so that more holes could be punched, which meant they could carry more data.

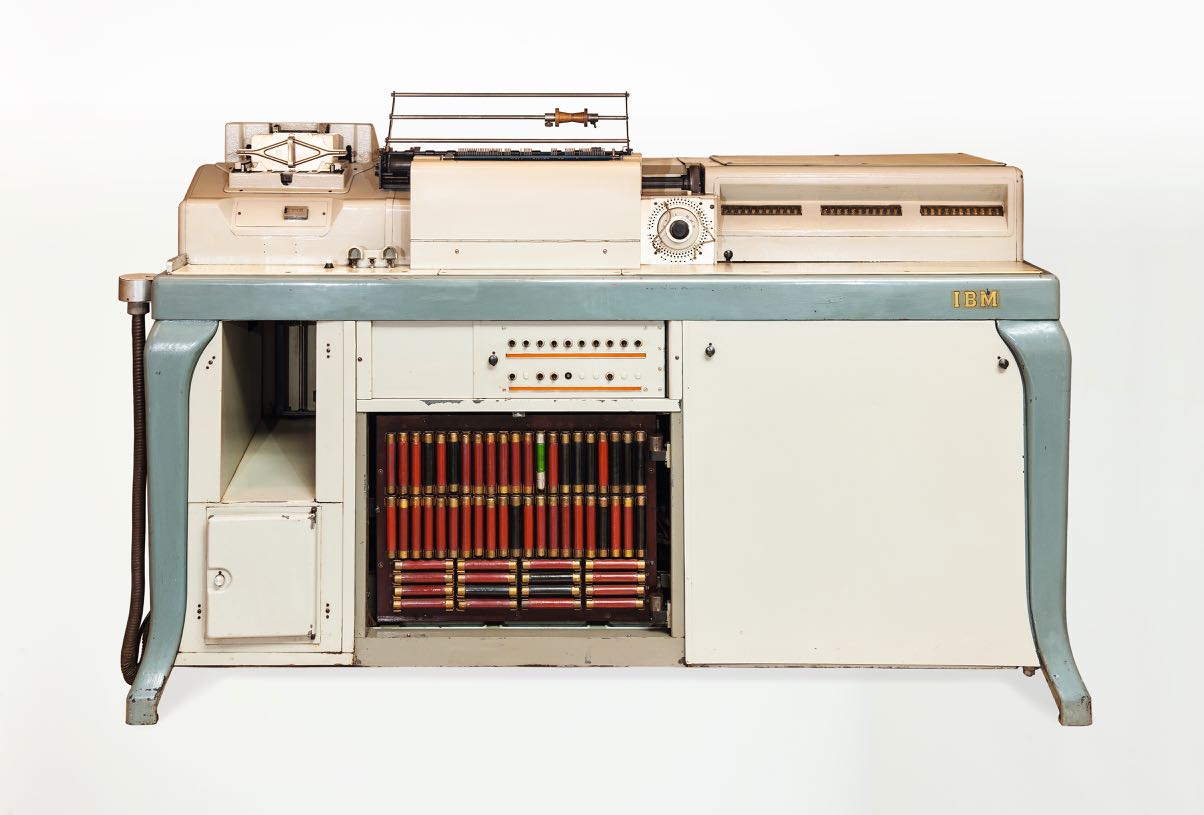

The D11 tabulating machine, which DEHOMAG first introduced onto the market in 1935, represented a true milestone in the history of punchcard technology. In Germany alone around 1,100 of these machines were produced by 1945. By means of so-called »intermediate operations« the course of the sequential calculating steps – a program – could be determined by variable electronic wirings on a plug board. But the most impressive features of the D11 were its ability to perform all four basic arithmetic operations and its arithmetic-logic unit being equipped with balance control. These made it attractive for the most diverse fields of application including, for example, the banking and credit sectors, commerce, industry and insurance. The piece exhibited at the Deutsches Technikmuseum had thus still been competent enough to be in use at the GDR State Insurance so many years later. The last version of this tabulator was sold under the name IBM D11 Type 450.

Shadows and light

In the first half of the 20th century, tabulators like the D11 rationalized the administrative process of the state and the economy to a huge extent. The high speed and precision of the counting and calculating processes enabled copious amounts of data to be handled while at the same time lowering costs. Thus companies established their own »Hollerith departments« from early on. Apart from that, the tabulators and puchcards continued to be indispensible for census taking. In the 1930s DEHOMAG had a monopoly on the machine data processing business in Germany. The company enjoyed the support of the National Socialist regime. It was thus more than happy to supply the machines, personnel and know-how for the 1933 and 1939 censuses – with the support and direction of its American parent company IBM. Tabulators from the IBM subsidiary were also in use in the Departments for Automated Reporting Systems including, for example, the NSDAP´s office of racial politics, the so-called »Judenreferat« (Jewish bureau) of the Reich Main Security Office responsible for the »Final Solution for the Jewish Question« and in concentration camps. They thus participated in the »total registration« of the Jewish people and the organization of the Holocaust.

It wasn´t long after 1945 that DEHOMAG went back into production. Demand for office and punchcard machines grew in the post-war years. The West German economic miracle kept the cash registers ringing even for DEHOMAG, which was renamed »IBM« after 1949. Production of the D11 wasn´t discontinued until 1960. As early as the beginning of the 1950s it became apparent that automated data processing was developing in another direction: The digital computer was poised to replace the electro-mechanical machines. Punchcards, however, continued to be used even in the coming digital age of mainframe computers. It was the higher storage capacity of magnetic tapes that finally spelled the demise of the punchcard around the mid-1960s.

Published in: Stiftung Deutsches Technikmuseum Berlin (Ed.): Net Matters. 30 Stories. From Telegraph Cables to Data Glasses, Berlin 2018.

Translation: Barry Fay, Lost in Translation

Object photography: Clemens Kirchner, Stiftung Deutsches Technikmuseum Berlin

Literature:

Black, Edwin: IBM and the Holocaust. The strategic Alliance between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation, London 2001.

da Cruz, Frank: Hollerith 1890 Census Tabulator, 2011. (accessed 17.10.2017)

Götz, Aly/Roth, Karl Heinz: The Nazi Census: Identication and Control in the Third Reich, Philadelphia 2004.

Petzold, Hartmut: Moderne Rechenkünstler. Die Industrialisierung der Rechentechnik in Deutschland, München 1992.